Hitchhiking with Zapatistas

Before I came to Mexico, I spoke with my father about how much my mother worries unnecessarily, and we agreed that I am to email her about my adventures only after they are done and I am once again safe in an Internet cafe. Then, he mentioned the unrest in the southernmost state of Mexico, foggily recalling the Zapatista movement, and I decided to say nothing about Chiapas for the time being. Of course, the exact place my parents didn't want me to go is my favourite area in Mexico. And, I am once again safe in an Internet cafe.

True, Chiapas is dangerous. In San Cristobal, an old colonial city high in the mountains, the sidewalks are worn slick, and in the drizzle they take on properties reminiscent of a Slip and Slide. The count: I fell twice, and so did my travelling companion. Locals seem a little surer on their feet. The sidewalks are also only wide enough for single-file walking. Maintaining conversational flow requires that one of the chatters walk in the narrow street. Walking in a narrow street in a country that affords all vehicles the right of way over pedestrians is perhaps the most dangerous thing one can do in Chiapas. Watch out for killer bicycles.

The incredible and accessible culture in and around San Cristobal provided a good reason not to wake up with a hangover or stay out all night listening to live reggae. Instead, my travelling friend and I stayed in at night to debate international politics with amateur ambassadors from many countries of the Western slant. And, to plan the next day's excursion.

After visiting the Museum of Mayan Medicine and climbing hundreds of stairs to view the city from its highest point, haggling at the market for already underpriced textiles, and being awestruck in a Mayan church (which deserves its own entry), we decided it was time to venture to the Zapatista village that was rumoured among the more lefty travellers to accept visits from foreigners - a sort of model village designed to educate outsiders about the new approach of the Zapatistas.

After visiting the Museum of Mayan Medicine and climbing hundreds of stairs to view the city from its highest point, haggling at the market for already underpriced textiles, and being awestruck in a Mayan church (which deserves its own entry), we decided it was time to venture to the Zapatista village that was rumoured among the more lefty travellers to accept visits from foreigners - a sort of model village designed to educate outsiders about the new approach of the Zapatistas.

We hailed a public truck in a busy market, on the periphery of the city, to take us there in the early afternoon, and rode more than an hour into the country side down terrifying winding and plunging roads. The roadside vistas punctuated by signs reading: You are now entering Zapatista territory.

Having met a Spanish national on the way, we three approached the farm-style gate and were immediately greeted by a guard in black balaclava, only his eyes exposed. He asked us what we wanted and we told him we were there to learn about their community and the movement. He nodded, asked for our passports and told us to wait. Several other covered men looked on and he disappeared into a small wooden building where, we later learned, he was asking permission for our entry. Upon his return we were escorted into another building for questioning. Several men entered the room, surrounded us and blocked the doorway. As much as I wanted to be comfortable and confident, being surround by black masks on the faces of warriors in a community established on reclaimed land, well, it's a little intimidating. Betraying me, my hands quivered. I reminded myself that the unknown is always the most frightening. And, that I was there in the community to make it known to me, to understand more. Besides, you don't have to see someone's mouth to know they are smiling. I relaxed. Then it was time. Time to be presented to the community government, or junta, for our education.

the doorway. As much as I wanted to be comfortable and confident, being surround by black masks on the faces of warriors in a community established on reclaimed land, well, it's a little intimidating. Betraying me, my hands quivered. I reminded myself that the unknown is always the most frightening. And, that I was there in the community to make it known to me, to understand more. Besides, you don't have to see someone's mouth to know they are smiling. I relaxed. Then it was time. Time to be presented to the community government, or junta, for our education.

A guard led us to the small wooden house, knocked, and motioned for us to enter. Here we were interviewed a final time, and approved. During the hour to follow, we listening attentively to the manifesto, delivered by a female and male representative of the junta. Well, really he did all the talking, and she napped throughout a portion. Who can blame her, though? How many times can one hear a manifesto?

Before I came to Mexico, I spoke with my father about how much my mother worries unnecessarily, and we agreed that I am to email her about my adventures only after they are done and I am once again safe in an Internet cafe. Then, he mentioned the unrest in the southernmost state of Mexico, foggily recalling the Zapatista movement, and I decided to say nothing about Chiapas for the time being. Of course, the exact place my parents didn't want me to go is my favourite area in Mexico. And, I am once again safe in an Internet cafe.

True, Chiapas is dangerous. In San Cristobal, an old colonial city high in the mountains, the sidewalks are worn slick, and in the drizzle they take on properties reminiscent of a Slip and Slide. The count: I fell twice, and so did my travelling companion. Locals seem a little surer on their feet. The sidewalks are also only wide enough for single-file walking. Maintaining conversational flow requires that one of the chatters walk in the narrow street. Walking in a narrow street in a country that affords all vehicles the right of way over pedestrians is perhaps the most dangerous thing one can do in Chiapas. Watch out for killer bicycles.

The incredible and accessible culture in and around San Cristobal provided a good reason not to wake up with a hangover or stay out all night listening to live reggae. Instead, my travelling friend and I stayed in at night to debate international politics with amateur ambassadors from many countries of the Western slant. And, to plan the next day's excursion.

After visiting the Museum of Mayan Medicine and climbing hundreds of stairs to view the city from its highest point, haggling at the market for already underpriced textiles, and being awestruck in a Mayan church (which deserves its own entry), we decided it was time to venture to the Zapatista village that was rumoured among the more lefty travellers to accept visits from foreigners - a sort of model village designed to educate outsiders about the new approach of the Zapatistas.

After visiting the Museum of Mayan Medicine and climbing hundreds of stairs to view the city from its highest point, haggling at the market for already underpriced textiles, and being awestruck in a Mayan church (which deserves its own entry), we decided it was time to venture to the Zapatista village that was rumoured among the more lefty travellers to accept visits from foreigners - a sort of model village designed to educate outsiders about the new approach of the Zapatistas. We hailed a public truck in a busy market, on the periphery of the city, to take us there in the early afternoon, and rode more than an hour into the country side down terrifying winding and plunging roads. The roadside vistas punctuated by signs reading: You are now entering Zapatista territory.

Having met a Spanish national on the way, we three approached the farm-style gate and were immediately greeted by a guard in black balaclava, only his eyes exposed. He asked us what we wanted and we told him we were there to learn about their community and the movement. He nodded, asked for our passports and told us to wait. Several other covered men looked on and he disappeared into a small wooden building where, we later learned, he was asking permission for our entry. Upon his return we were escorted into another building for questioning. Several men entered the room, surrounded us and blocked

the doorway. As much as I wanted to be comfortable and confident, being surround by black masks on the faces of warriors in a community established on reclaimed land, well, it's a little intimidating. Betraying me, my hands quivered. I reminded myself that the unknown is always the most frightening. And, that I was there in the community to make it known to me, to understand more. Besides, you don't have to see someone's mouth to know they are smiling. I relaxed. Then it was time. Time to be presented to the community government, or junta, for our education.

the doorway. As much as I wanted to be comfortable and confident, being surround by black masks on the faces of warriors in a community established on reclaimed land, well, it's a little intimidating. Betraying me, my hands quivered. I reminded myself that the unknown is always the most frightening. And, that I was there in the community to make it known to me, to understand more. Besides, you don't have to see someone's mouth to know they are smiling. I relaxed. Then it was time. Time to be presented to the community government, or junta, for our education. A guard led us to the small wooden house, knocked, and motioned for us to enter. Here we were interviewed a final time, and approved. During the hour to follow, we listening attentively to the manifesto, delivered by a female and male representative of the junta. Well, really he did all the talking, and she napped throughout a portion. Who can blame her, though? How many times can one hear a manifesto?

Satisfied with our behaviour and interest, the junta rose to shake our hands and we thanked them with the only Mayan words we knew. They set us loose in the community, encouraging us to take pictures and return to our countries to spread the word that they are a non-violent, peace-loving people. I thought about how worried my parents would be if they knew I was there.

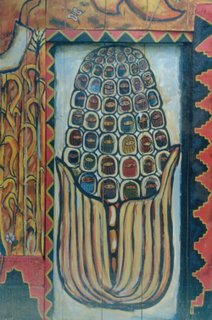

The farming community was quiet and colourful. Most of the buildings were painted with images of people, representing all races and two sexes, happily together in territorio libre. But, unfortunately, I was preoccupied.

The entire ordeal had taken long enough that I could now think only of finding a bathroom. There was none to be found. We were going to have to ask the guards. Still in balaclava, several were napping on sheets of cardboard next to the road entering the village. Understanding the urgency of our plight, one guard took it upon himself to search the village with us to find one that was functioning. As we searched, we came upon two more touristas with the same problem. Soon, he had a trail of women chasing him through the farm village, trying to convince him that we were not adverse to peeing in bushes. Just in time, however, he located one and returned to his napping post. It had been a close call for some of us.

Later on, as we browsed the souvenir shop, we wondered how much of the day had been pageantry, and how much was inspired by the fact that they are still considered an illegal entity. We bought a coffee from the general store/cafe and asked when the last collectivo, or public bus, would be passing through. Per usual, no one really knew, and, as the sun was beginning to set we thought it best to head out.

We waited. And, we waited more. And, longer.

Eventually, we began flagging down pick-up trucks of workers and melons, asking them if they were returning to San Cristobal. None were.

We waited. We began wondering what it might be like to sleep in the woods in the southernmost mountainous region of Mexico. Too cold, we concluded.

Soon, a local man came to the roadside, smiled at us, flagged down a speeding Volkswagen Beetle and said, "San Cristobal?" Recognizing his clothes and eyes, we nodded and hopped in. The driver appreciated the company, and described to us his coffee exportation business, encouraged me to marry a Mexican, and debated politics with this Zapatista guard new friend of ours as we zipped over the same winding road that brought us there, usually on the wrong side.

Arriving safely in the city, we rushed to the bus station and caught the next ride to the jungle. We were set to arrive in the middle of the night, with no place to stay. If the trip continued like this, I thought, I won't be able to tell my poor parents any of it.

Later on, as we browsed the souvenir shop, we wondered how much of the day had been pageantry, and how much was inspired by the fact that they are still considered an illegal entity. We bought a coffee from the general store/cafe and asked when the last collectivo, or public bus, would be passing through. Per usual, no one really knew, and, as the sun was beginning to set we thought it best to head out.

We waited. And, we waited more. And, longer.

Eventually, we began flagging down pick-up trucks of workers and melons, asking them if they were returning to San Cristobal. None were.

We waited. We began wondering what it might be like to sleep in the woods in the southernmost mountainous region of Mexico. Too cold, we concluded.

Soon, a local man came to the roadside, smiled at us, flagged down a speeding Volkswagen Beetle and said, "San Cristobal?" Recognizing his clothes and eyes, we nodded and hopped in. The driver appreciated the company, and described to us his coffee exportation business, encouraged me to marry a Mexican, and debated politics with this Zapatista guard new friend of ours as we zipped over the same winding road that brought us there, usually on the wrong side.

Arriving safely in the city, we rushed to the bus station and caught the next ride to the jungle. We were set to arrive in the middle of the night, with no place to stay. If the trip continued like this, I thought, I won't be able to tell my poor parents any of it.

No comments:

Post a Comment