Cuba: A 36-hour fiasco

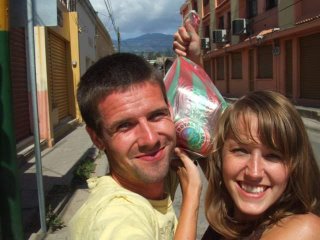

It wasn’t my idea. None of it. Not the trip. Not the tequila. Not the nudity. Nor was it my fault. Not the interrogation with Customs officials. Not the suntan lotion fight. Not the loss of the plane tickets or injuries sustained. I did, however, contribute.

It was a most unconventional trip. Upon accepting the offer, I knew it would be difficult to explain the impromptu weekend getaway (at an all-inclusive Cuban resort) to my friends and family.

I imagined saying, "Well, there’s this guy who knows people I know, who wants to take my friend and me to Cuba for the weekend, basically for free."

And, in response to their questions, answering:

"It’s an employment perk – he works for an airline."

"No, I don’t personally know him."

"No, there won’t be separate rooms."

"Well, he saw us at a gallery opening and thought we looked fun."

"No, not that kind of fun. I don’t think so anyway."

And then somehow justifying my decision to go.

My friend, Anna and I, of course, conducted an informal background check. We spoke with people who knew him relatively well, asked for rumours of possible misdeeds, and investigated his “My Space” online profile. Following a full-scale, covert evaluation of his creep-factor, we established it would be OK to go.

Our first actual encounter with Rick, at a local bar the night before our scheduled departure, allowed us to further scrutinize him and his possible intentions. Perhaps we were too trusting, perhaps too hopeful, or, perhaps we are simply good judges of character, but we confirmed the trip when he was kind enough to buy us a drink, but did not encourage us to drink too much.

Parting ways that evening, my friend and I joked about rumours this could inspire, and how annoyed his straight male friends must be that he is able to offer weekend getaways to women he meets. We were pleased with our spontaneity, confident in our decision, and curious whether he would regret taking us to the Caribbean.

Parting ways that evening, my friend and I joked about rumours this could inspire, and how annoyed his straight male friends must be that he is able to offer weekend getaways to women he meets. We were pleased with our spontaneity, confident in our decision, and curious whether he would regret taking us to the Caribbean.True, we weren’t looking forward to the eight-hour overnight stopover in Toronto’s International airport, but we are hardy travellers and determined make the best of it, whatever “it” may be. Rick was equipped to help us do that. A frequent flyer, he knew which bars were nearest to the hotels served by the free airport shuttle bus. We passed a few hours getting to know each other in the netherworld of a Mississauga tavern and, two drinks later, we were better prepared to sleep in the airport and await the 4 a.m. check-in.

We didn’t know it, but it was then that the fiasco truly began.

Feeling very casual about the quick weekend jaunt, we piled our little overnight bags onto the conveyor at the airline counter in no particular order. We didn't pay attention to which bag was tagged with which name.

I slept through the entire four-hour flight, waking only once with Anna’s help to enjoy a spongy omelette. Exhausted as we disembarked, I imagined napping happily on the beach, pretending to feel guilty about getting too much sun, and gorging myself on the buffet.

This was my fourth trip to Cuba and I was comfortable with the stony stare of Customs officials and lengthy entrance procedure. I was prepared to collect the bags quickly, exchange money and head straight for the sand. I was not prepared for a two-hour interrogation.

Anna was the first to be searched. Rick was second. Following the flow of excited

vacationers, as I’d done during previous visits, I headed for the exit. A Customs official stopped me and asked to see my papers. Apparently, the brevity of our stay had roused suspicion. My Canadian passport, valid for six years, expires this December. I’ve travelled a lot and, just this year, visited 10 Latin American countries, from Mexico to Argentina. The man in khakis asked me about every nearly illegible entry and exit stamp.

vacationers, as I’d done during previous visits, I headed for the exit. A Customs official stopped me and asked to see my papers. Apparently, the brevity of our stay had roused suspicion. My Canadian passport, valid for six years, expires this December. I’ve travelled a lot and, just this year, visited 10 Latin American countries, from Mexico to Argentina. The man in khakis asked me about every nearly illegible entry and exit stamp.While my travel partners were still explaining the contents of their bags, including a copy of The Catcher in the Rye – an unfortunate choice of beach-reading for Cuba – I was escorted to a private room.

An officer with glittery, gold acrylic nails and a government-issue khaki miniskirt asked me to empty my bags. She flipped through my book, read my bits of paper, analyzed the contents of my make-up case and shook my bottle of ibuprofen. She questioned me in Spanish and recorded every mispronounced word I said. My answers, as innocent as they actually were, roused more and more suspicion.

She wanted to know if I was a journalist.

I'm not. Hmm.

Had I ever been to Cuba before?

Yes. Wrong answer.

How many times?

Three times. Wrong answer.

When was my last visit?

I can’t remember---a few years ago. Wrong answer.

Why did you travel so much this year?

To learn Spanish. Right answer.

Why are you only staying for the weekend?

Because we got a deal and it was really cheap. Hmmm.

And, why doesn’t your baggage tag match the one on your ticket?

I don’t know. Wrong answer. Shit.

I explained that our tags must have been switched in Toronto during check-in. She instructed me to find my travelling companions and retrieve their tickets to corroborate my claim. I re-entered the airport lobby and saw Rick still justifying his possessions and trip length. The Customs official with him called me over. Hablas español? Si, mas o menos.

In less than a minute I was able to explain that Rick was an airline employee. Thanks to me, he was released. I, however, was returned to the interrogation room, which I now shared with a foreign doctor caught importing a suitcase of pharmaceuticals. Another hour later, following full assessment of my capitalist-creep-factor, I was granted entry to the country. The doctor was released before I was.

We caught the last shuttle to our resort and I was disappointed to learn that this was no party bus. Anna claimed she intended to buy beer for the 45-minute ride while I was detained, but Rick thought it might be insensitive. We teased him about his poor decision-making skills and declared we’d never go on a free trip with him again. Engaging a beer-guzzling fellow bus passenger, I stated that some travellers were clearly more prepared than others. Buying in, the vacationer offered me a can of my own. Tepid and watery, my first cerveza was divine.

Our resort was the last on the circuit and our driver, anxious to end his shift, was stopped by the tourist police for speeding. The bus crawled the final 5 km, and we were relieved that the fairest resort of all would be ours for the remaining 34 hours of our trip. We intended to take full advantage of its virtues.

Within the first hour, we discovered fresh fish and calamari at the beach grill. Within the first two, we discovered that hotel staff allowed us to bring entire bottles of sparkling wine to the beach. Their leniency--- and the piña coladas, mojitos, daiquiris, white wine and tequila---inaugurated Stage Two of the fiasco. Let’s be reasonable, a 36-hour vacation does not afford time for moderation.

Within the first hour, we discovered fresh fish and calamari at the beach grill. Within the first two, we discovered that hotel staff allowed us to bring entire bottles of sparkling wine to the beach. Their leniency--- and the piña coladas, mojitos, daiquiris, white wine and tequila---inaugurated Stage Two of the fiasco. Let’s be reasonable, a 36-hour vacation does not afford time for moderation.The buffet was delicious. Anna and I nourished our pancitas---literally meaning, “little breads” and synonymous with “little bellies”---while a group of plump Russian men eyed her from the adjacent table and mimed concern that our male companion might be dating one of us. Sharing no common language, Rick thought it best to mime that he was dating both of us and that we were, therefore, unavailable.

Not easily discouraged, the nearest Russian employed drastic and disturbing means to woo Anna. He unbuttoned his shirt and revealed a pectoral that was likely impressive during his weight-lifting career, but had long since retreated far beneath a fatty mound of hairy flesh. He flex-bounced this atrocity in her direction, smiling, until Rick reached over and poked it. The Russian struggled to express that he was not a homosexual, but that Rick probably was, and put his breast away. For the rest of the meal, they focussed their attention on the troupe of Colombian prostitutes that occupied a table in the opposite direction. We thanked Rick for the risk he took in defending our honour from these mafiosos.

Satisfied, we headed for the lobby bar to decide what to do with our one-night-in-paradise. As we settled into seats farthest from the merging gaggles of Russians and Colombians, the bartender declared it was “Tequila Time”. Lacking shot glasses, he improvised with champagne flutes, and refilled them in 10-minute intervals. I blame the bartender entirely for all events that followed.

We zigzagged to our room to freshen up and decide whether venturing to a salsa club was feasible. In the meantime, Anna discovered the comforts of the king-sized bed and fell asleep. Unsure about how to motivate her, I tried everything: reasoning, guilt, poking, wedgies; nothing worked. If comfort was keeping her in bed, I would just have to make her uncomfortable. That’s why I filled her ears with suntan lotion. No one wants to sleep with cream in their ears. Tequila was doing the thinking for me.

This friend, while petite, is a powerhouse. I hadn't anticipated the speed or violence of her attack, but within seconds the lotion was turned on me and my clothes were ruined. Collectively, we agreed that staying on resort grounds was the safest idea, considering the repercussions of “Tequila Time”. Swimming in the lake-sized pool---among its concrete islands and sculptures---was the new clandestine activity of choice. At other resorts I’ve visited, pools are off-limits at night and I wasn’t sure about this one. Just in case, we planned the outing as a stealthy, strategic operation; only, tequila doesn’t exactly make you smarter, or quieter.

We piled our clothes and shoes in the shadows behind the closed pool bar, and Rick ducked in to check the beer taps. Likely for the best, they were locked. We cautiously entered the pool and bobbed around for a while, but soon remembered how much better drinks taste when free, and headed to the bar in our suits and trunks, soaking wet.

“Were you in the pool?” asked the barman.

“Noooooooo. Nooooo-no-no-no,” I said, unable to think of any believable excuse for being wet.

He squinted at us, so I distracted him with conversation. I thought I was speaking Spanish, but thinking back, I’m not so sure. The mafia and prostitutes were nowhere to be seen and the bartender seemed a little lonely, which surely increased his tolerance for us. Soon another nightshift worker showed up and announced, “The name’s Willy, but you girls can call me Big Willy.” Apparently to justify the nickname, Big Willy propped a flabby leg atop the barstool beside me in what Rick later described as “an incredibly revealing, revolting position”. I didn’t notice. I was busy pretending we hadn’t been swimming in the pool.

Like divine intervention, a brief torrential downpour interupted Big Willy's wooing, and Rick realized we’d not only left our clothes behind, but also his digital camera. Running off to its rescue, he made it only a few steps from the bar before slipping on the wet walkway and falling to the ground. And there he stayed.

Concerned the bartender would deem us too inebriated to continue our evening, I dismissed the incident as normal, “Oh, you know, he just, um, falls sometimes.” The tequila was talking again. Realizing Rick wasn’t getting up on his own, Anna ran to check on him while I distracted Big Willy and the bartender with what remained of my conversational skills. “Nice tattoo,” I heard myself say in Spanish.

Rick rose and hobbled off into the rain with an injury that would leave him limping for a week. Apparently inspired by his misfortune, Anna skipped back to the bar and lay on the floor, laughing. Again I suggested this was normal. “She just, um, you know, likes it on the floor.” Then, as if it would enhance the credibility of my claim, I got down beside her and awaited Rick’s return. Tequila was now also doing the reasoning.

Convinced we'd duped the staff, we requested a final bottle of wine-to-go. It was the last that remained and, thinking back, I'm appalled they actually gave it to us. Confident that no one would follow, we headed back to the pool and I ducked into the shadows to remove my bathing suit. Tequila told me skinny-dipping was a treat to be discreetly enjoyed whenever possible. I believed it. I also believed that no one would know I was naked as long as I was immersed in water. Anna seconded my theory and we abandoned our last bits of modesty at the poolside, forgetting, of course, to take note of the location. Off we swam.

Rick also enjoyed the fruits of naked swimming, but was either gentlemanly or frightened of us, and he maintained a safe distance. Emerging from the water to retrieve the already-forgotten wine, he turned to avoid flashing us. It was then that he accidentally exposed himself to the bartender, who had thoughtfully delivered us an ice bucket to chill the wine. What service! Mentioning nothing of nudity, the bartender retreated. Rick scrambled to replace his trunks and warn us, but it was too late. By the time he found us, we had already succumbed to the temptation of the pool centrepiece---a large sculpture designed to look like a beach recliner. And on it we stood.

Four resort employees, all male, had gathered at the poolside and were calling us over. “Just act casual,” said the Tequila.

Since no one addressed our state of undress, I figured the friendly staff hadn’t noticed. “It’s really dark out; they probably just think you’re wearing a white bathing suit,” reasoned the Tequila again. I chatted in Spanish with the workers, I think, and vaguely recall a marriage proposal.

Seemingly out of nowhere, Rick reappeared with a vaguely panicked look on his face. “Listen to me. Put. This. On. NOW,” he said, placing emphasis on every word and handing me my bikini. I responded to his kindness and rationality by mocking him. Nevertheless, I donned my bikini bottoms underwater with relative ease. It was the top that was complicated. Anna had already replaced her own.

Completely covered, and convinced no one suspected anything less of us, we agreed with Rick’s suggestion that we return to our room and call it a night. Anywhere else on the resort and we’d be stuck talking with the staff. It seemed they liked us. As it was, they all insisted on escorting us back to our room. Someone had the presence of mind to grab our clothes, shoes and the wine. Once Anna and I were safely inside, the staff gave Rick an enthusiastic thumbs-up, for what their wishful thinking wanted to happen next. They couldn’t have been more misled.

Unconscious almost immediately, the wine untouched, we all slept soundly (very, very soundly) until noon the next day. Rushing to check out on time, we shook the leaves from our scattered belongings, stuffed wet clothes into our overnight bags and headed to the front desk, apparently looking our absolute worst. The receptionist avoided eye contact. Our return flight to Montreal wasn’t leaving until that evening, so we stashed our bags and returned to the beach to enjoy more grilled seafood and hair-of-the-dog, and discuss the previous night.

“You aren’t ever going to take us anywhere ever again are you?” Anna asked Rick.

“Are you kidding?” was his only response.

We napped in the ocean. We napped on the beach. We napped under the shade of the umbrella that tricked Rick into thinking he wasn’t turning a frightening and painful shade of pink.

Giving ourselves just enough time to get to the airport, we retrieved our bags and changed our clothes. During this process we realized no one had the plane tickets.

Staying only one night, we didn’t bother using the safe; we stashed the tickets on top of the television instead. Or rather, I did. I think that part was fine. It was the fact that no one picked them up in the morning before we checked out that created the problem. The cleaning staff must have thrown them out. We approached a security guard for help.

“Room 125?” he asked. I hadn’t told him. It was just as I’d feared; we were notorious.

He helped us double-check the room and our bags and called the cleaning staff---nothing. Shit. This was the beginning of the final stage of the fiasco.

With no alternative, we headed to the airport by taxi ($35 in Cuban Convertible Pesos---roughly equivalent to $40 USD), to convince the airline to let us on the plane without tickets.

There was another challenge. Cuba doesn’t stamp passports upon entering the country. Instead, tourist visas are issued on separate pieces of paper and collected when the visitor leaves. Our tourist visas were with our plane tickets. We had no evidence that we’d entered Cuba legally.

At this point, both Rick and Anna had nearly run out of cash and we all needed to pay a standard $25 tax to leave the country. There are no automatic bank or debit machines in Cuba, and none of us had valid credit cards to withdraw money. We pooled our funds and came out $20 short. After investigating all possible alternatives, we realized one or all of us, would have to remain in the country if we didn’t somehow procure the funds. I was already hoping it wouldn’t be me when Anna announced she would go to Havana. Tequila was, apparently, still doing some of our thinking.

Following the first stressful hour at the Cuban airport, an airline representative recognized Rick’s name from company files, and agreed to reissue our tickets. With this first problem solved, we focussed on the second challenge.

Most of the passengers had already passed through security into the departure lounge, and time was running out. I would need to swallow my pride and explain my ineptitude in exchange for sympathy and donations. I approached a young couple about to check in. As I listened to myself describe our predicament, I realized how ridiculous we were.

“I’m sorry,” said the man. My heart sank below sea-level before he continued with, “I only have $20 Canadian to give you. You’ll need about $5 more.”

I couldn’t believe my luck. I’d chosen the most stereotypical, overly-apologetic, eager-to-please Canadians in the airport. They felt terrible for not helping us enough. Then, they remembered the Cuban coins they packed as souvenirs and offered those to us, too. We had exactly the amount we needed. I asked for their mailing address so we could reimburse them upon our safe return, but they were so pleased with themselves for helping us, I don’t think they cared. We’d already given the couple a story to tell for years to come; one that would likely become more melodramatic each time it was recounted. They’d already started retelling it to us. It was a tale of three frightened fellow Canucks trapped in post-9/11 Castro-era Cuba. Remember that, Honey? Remember how we rescued them from Communism?

Relieved and grateful regardless, we announced the news to Rick like kids with candy, under the affectionate watch of our Canadian sponsors. He responded with, “We have a problem.” Shit.

The airline required $80 in cash for the new tickets. I scanned the airport for more potential donors and addressed the airline representative, “That is just not possible.” In a rare display of Cuban leniency, she agreed to bill Rick later. I think he’d been flirting.

Once again we were escorted to a special section of Customs, where we handed over our passports, questioned and told to wait. We waited and waited and wondered whether we’d miss the flight anyway. The Customs official returned with mere moments to spare and, with the familiar stony stare, handed us papers that legally excused our incompetence. We were instructed to exit through regular Cuban security one last time.

“You arrived yesterday?” asked the confused officer who collected my exit papers. “What can you possibly do in just 36 hours?”

Thankfully, my bloodshot eyes and the sorry state of my travelling companions answered for me. I wouldn’t have known where to begin.